Anatomy of an Autonomous Gold Farming Operation

For two years, I built a system that ran an entire business autonomously. Up to 18 bots across GPU-VPS instances and local NUCs farmed gold in World of Warcraft, posted eBay auctions with dynamic pricing based on real inventory, processed buyer orders using GPT-4o to extract character names from freeform messages, delivered gold in-game via a coordinated bot fleet, uploaded proof-of-delivery screenshots, and marked eBay orders as fulfilled. All I had to do was watch.

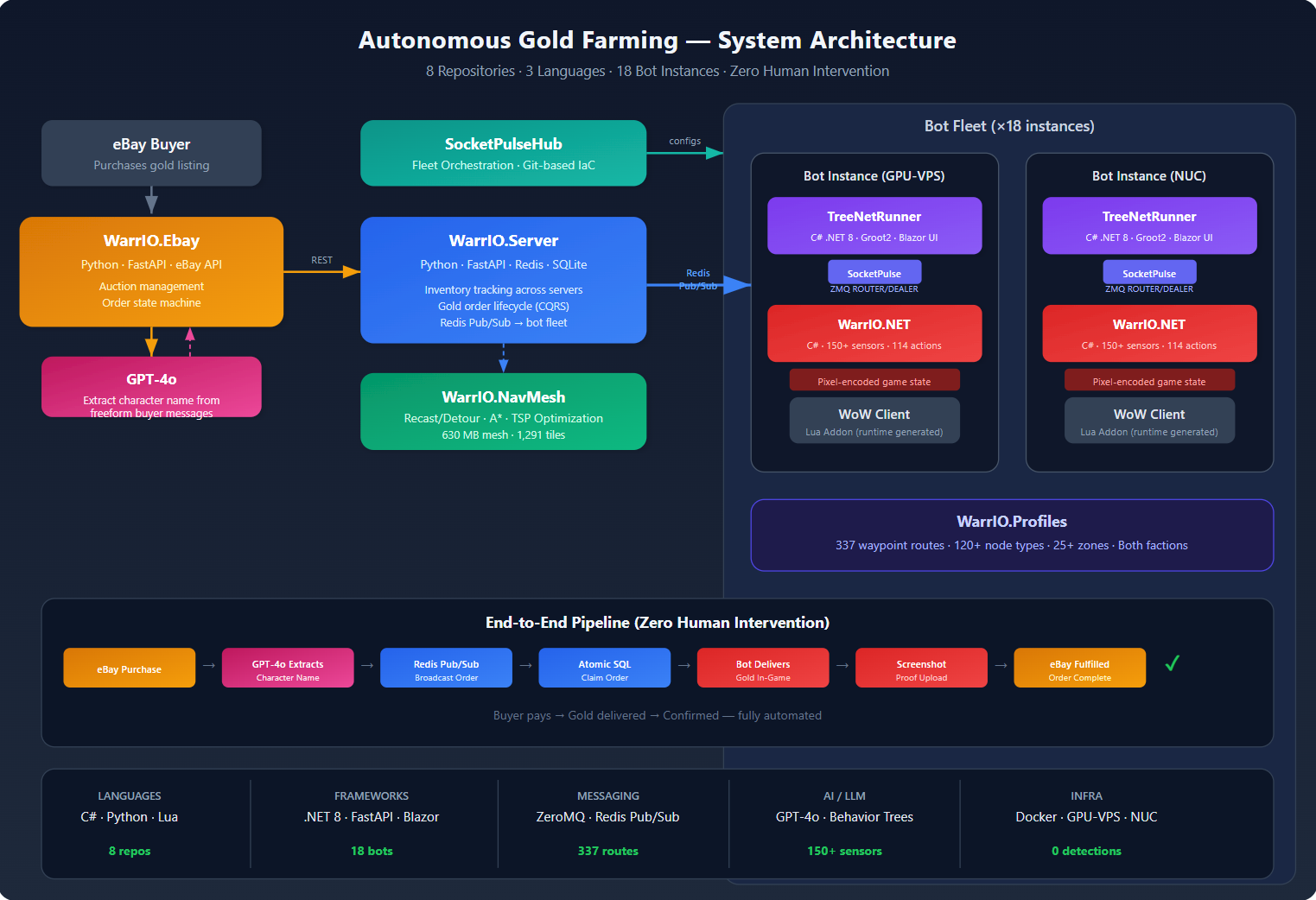

This post is about the engineering — not the game, not the economics. The architecture I ended up with spans 8 repositories, 3 programming languages, and touches behavior trees, ZeroMQ messaging, pixel-based game state encoding, runtime Lua code generation, A* pathfinding on navigation meshes, and LLM-powered text extraction. It's the most complex system I've ever built, and it taught me more about autonomous systems than any enterprise project.

How It Started: A Bot to Keep Up With Friends

The first version of this bot had nothing to do with making money. I had a full-time job while some of my friends were still students. They could play WoW all day. I couldn't. The only way to keep up with their leveling speed was to automate mine.

So I wrote a bot in C++ — because C++ was the language I loved. It started simple: follow waypoints, kill mobs, loot, repeat. Over time it grew more capable. At some point the bot was farming so efficiently that it was accumulating gold I didn't need. Selling it on eBay wasn't planned — it just made sense. The bot was already running. The gold was already there. Why not?

That C++ bot eventually hit 1,000 EUR/month on eBay. But it was a monolith. One process, one machine, one game instance. Scaling meant running more copies of the same executable, manually configuring each one, with no coordination between them. When I wanted multiple bots to share gold, trade with each other, or claim delivery orders from a central queue — the single-process C++ architecture couldn't support it.

The C# rewrite wasn't about language preference — it was about distribution. I needed bots that could run on separate machines, communicate over networks, coordinate through a central server, and be deployed and updated remotely. C# with .NET gave me the ecosystem for that: ZeroMQ bindings (NetMQ), dependency injection for clean modular design, reflection for dynamic command discovery, and mature tooling for everything from web APIs to process management.

The rewrite took the better part of a year. But the resulting system could do something the C++ bot never could: scale horizontally. One behavior tree engine, one communication protocol, one deployment system — running 18 bots across GPU-VPS instances and local NUCs, all coordinated through a central server.

The other design goal that made the rewrite worth it: I built v2 as a reusable botting framework. TreeNetRunner and SocketPulse are completely game-agnostic. The behavior tree engine doesn't know it's playing WoW. I could build bots for other games by just implementing the receiver interface — the entire orchestration layer, behavior tree system, and deployment infrastructure would carry over unchanged.

The System at a Glance

Here's what the full pipeline looks like: eBay buyer purchases gold → WarrIO.Ebay detects the paid order → sends buyer a message asking for their character name → buyer replies with something like "its thrall on thunderstrike thx" → GPT-4o extracts the structured data → WarrIO.Server creates a gold transaction order → Redis Pub/Sub broadcasts to the bot fleet → a bot claims the order via atomic SQL → navigates to a mailbox and sends the gold → uploads a screenshot as proof → WarrIO.Ebay confirms fulfillment to the buyer and marks the eBay order as shipped.

Zero human intervention from purchase to delivery.

The system is split across 8 repositories:

| Repository | Language | Role |

|---|---|---|

| TreeNetRunner | C# (.NET 8) | Game-independent behavior tree engine |

| WarrIO.Profiles | XML/JSON | 337 waypoint files, 120+ node types |

| SocketPulse | C# (.NET 7) | Custom ZeroMQ IPC library |

| WarrIO.NET | C# (.NET 7) | Game client interface |

| WarrIO.NavMesh | Python + C# DLL | Pathfinding server (Detour) |

| WarrIO.Server | Python (FastAPI) | Central coordination hub |

| WarrIO.Ebay | Python (FastAPI) | eBay marketplace automation |

| SocketPulseHub | Python (FastAPI) | Fleet deployment & orchestration |

Let me walk through the most interesting engineering decisions in each layer.

1. The Framework: Making It Game-Independent

Early on, I made a decision that shaped everything: the bot framework should know nothing about WoW. TreeNetRunner — the behavior tree execution engine — sends named commands over a socket and gets back success/failure/running responses. It has no idea what "Walk" or "HandleCombat" means.

This separation is achieved through SocketPulse, a custom IPC library I built on top of ZeroMQ's ROUTER/DEALER pattern. The protocol is dead simple:

// Request (TreeNetRunner → Game Client)

{

"Type": "Action",

"Name": "Walk",

"Arguments": { "direction": "north", "distance": "10" }

}

// Reply (Game Client → TreeNetRunner)

{

"State": "Success",

"Content": null

}

Three command types: Actions (do something, return success/failure), Conditions (check something, return true/false), and Data (query something, return a string). That's the entire API surface. Game-specific logic lives entirely in the receiver — which in this case is WarrIO.NET, but could be anything that implements IAction, ICondition, and IData.

Command handlers are discovered at runtime via reflection. Drop a new class implementing IAction into the assembly, and it's automatically available as a behavior tree node. No registration, no config files.

// This is all you need to add a new game action

public class CookFood : IAction

{

private readonly GameActor _gameActor;

public CookFood(GameActor gameActor) => _gameActor = gameActor;

public State Execute(Dictionary<string, string> arguments)

{

_gameActor.CookFood(arguments["foodName"]);

return State.Success;

}

}

TreeNetRunner picks up the tick rate from the receiver via a GetTickRate data command, so the behavior tree runs at whatever frequency the game client can handle. Typically 100ms — 10 ticks per second.

Why ROUTER/DEALER instead of simpler REQ/REP? Reliability. REQ/REP can hang if either side crashes mid-exchange. ROUTER/DEALER tracks client identity explicitly, handles reconnection gracefully, and doesn't deadlock on partial messages. I learned this the hard way after the first version used REQ/REP and would occasionally freeze the entire bot.

2. The Behavior Trees: 337 Routes and 120 Node Types

The bots don't run scripts — they run behavior trees authored in Groot2, a visual editor. The trees are stored as XML and loaded by TreeNetRunner's FluentGrootParser at startup.

Here's what the top-level decision logic looks like:

<Fallback>

<Sequence>

<IsGoldOrderActive/>

<SubTree ID="GoldOrderRoot"/>

</Sequence>

<Sequence>

<IsBankCharacter/>

<SubTree ID="BankingRoot"/>

</Sequence>

<Sequence>

<PlayerLevelBelow level="60"/>

<IsAlliance/>

<SubTree ID="ClassicLevelingRoot"/>

</Sequence>

<Sequence>

<PlayerLevelBelow level="60"/>

<SubTree ID="ClassicHordeLevelingRoot"/>

</Sequence>

<Sequence>

<CookingLevelBelow level="300"/>

<SubTree ID="CookingFishingRoot"/>

</Sequence>

<Fallback>

<SubTree ID="EndGameRoot"/>

</Fallback>

</Fallback>

The tree dynamically switches between leveling, profession training, banking, gold order delivery, and endgame farming based on character state. A level 35 Alliance character runs the leveling tree. A level 60 with maxed cooking runs the endgame farming loop. A bank character processes mail and posts auctions. All from the same root tree.

337 JSON waypoint files define navigation routes across 25+ WoW zones. Each file is a list of [x, y] coordinates forming patrol circuits, travel paths between hubs, or grinding loops. The naming convention tells the story: BurningSteppes_Area1Grind.json (86-waypoint farming loop), Wetlands_DarkshoreShipToDocks.json (cross-continent travel), Felwood_SpiritHealerToGrazle.json (death recovery route).

The behavior trees handle both factions — 17 zones for Alliance leveling, 10 for Horde — with separate profession chains for cooking, fishing, herbalism, and alchemy. Each zone has repair checkpoints, food/water buy points, innkeeper bindings, and class trainer visits wired in.

Anti-Detection Through Behavior

One subtle but important design: iteration limiting.

<HasReachedIterationLimit

identifier="Felwood Nodes"

limit="2"

timespanHours="3"/>

The bot tracks how many times it's farmed a specific route within a time window. Two Felwood herb runs per 3 hours, then it moves on to something else. This prevents the obvious bot pattern of running the same circuit 24/7. The behavior tree naturally rotates between zones, professions, and activities — looking much more like a human player with varied interests.

The ALT+F4 Incident

Early in development, I set up keybindings that used modifier keys — including ALT combined with function keys. The bot would happily use ALT+F1 through ALT+F3 for various abilities. Then one day, a behavior tree path led it to ALT+F4.

I spent hours debugging why the bot kept "crashing" at random intervals before I realized it was diligently closing its own game window. The fix was trivial — blacklist ALT+F4 — but the debugging session was not.

When Players Talk to Your Bot

One of the more surreal aspects of running bots at scale: other players would chat with them. The bots had simple automated responses to common messages — short, vague replies that didn't commit to anything. Players would have entire conversations without ever suspecting they were talking to a bot. Nobody reported them.

This accidentally taught me something about conversational AI years before ChatGPT: people don't need sophisticated responses. They need responses that feel plausible. A short "thx" or "yeah" is enough to satisfy most social interactions.

3. The Game Interface: Encoding State as Pixels

This is the part I'm most proud of from an engineering perspective.

The standard approach to game botting is memory reading — scan the game process's memory for known offsets that contain player health, position, inventory, etc. The problem: anti-cheat systems like Warden specifically look for external processes reading game memory.

My approach: don't read memory at all. Instead, generate a Lua addon at runtime that reads game state through WoW's legitimate API and encodes it as pixel colors on screen. Then read those pixels from outside the game using standard Windows GDI calls.

Here's how it works:

- WarrIO.NET generates a Lua addon at startup, dynamically built based on character class, level, and current quests

- The addon runs inside WoW as a legitimate UI modification

- Each frame, the addon writes game state values to individual pixels in a hidden UI frame — pixel 0 might be player health percentage, pixel 1 is mana, pixel 2 is X position, etc.

- WarrIO.NET reads the top pixel row of the game window via

BitBlt+GetPixel(Windows GDI) - Each pixel's 24-bit color value decodes to a sensor reading

// Read game state: capture top pixel row, decode values

public int GetPixelValue(BaseSensors sensor)

{

int pixelIndex = _addonState.GetSensorPosition(sensor);

int colorValue = _pixelReader.GetPixel(pixelIndex);

return colorValue >> 8; // Drop alpha channel

}

The addon is dynamically extended at runtime. When the bot encounters a new quest, WarrIO.NET generates additional Lua code to track that quest's completion status, writes it to the addon folder, and triggers a /reload in-game. The addon grows with the bot's needs.

150+ sensor types are encoded this way: player health, mana, position, facing angle, target info, combat state, bag contents, quest status, profession skill levels, auction house prices, mailbox status, group member positions, and more.

For text extraction (player names, chat messages, item names), the addon converts strings to numeric values character-by-character and spreads them across multiple pixels. The C# side reassembles them.

Why This Is Hard to Detect

- No memory reading — Warden's primary detection vector is neutralized

- No DLL injection — WarrIO.NET runs as a separate process

- The Lua addon uses only legitimate WoW API calls — it's technically just a UI mod

- Pixel reading via GDI is a standard Windows operation, not game-specific

- The addon looks like any other custom UI when inspected

And here's the result that validates the approach: I was never detected by Blizzard's anti-cheat. Not once. The entire codebase was written from scratch — no copied code from public bot frameworks, no shared signatures for Warden to fingerprint. Every bot that uses publicly available frameworks shares detection signatures. Mine didn't share anything with anyone.

Finding Blizzard's Bugs

Running bots 16 hours a day across 18 instances turns you into an involuntary QA department for Blizzard. I always knew when a new patch dropped — because something would break. But not my code. Blizzard's Lua API would change in undocumented ways, or outright break.

After the Microsoft acquisition and the resulting team changes, the frequency of Lua API bugs noticeably increased. Functions that had worked for years would suddenly return nil, event handlers would fire with wrong arguments, or timing-sensitive operations would silently fail. I maintained a growing collection of workarounds for Blizzard's own bugs — which, ironically, made my bot more robust than the game's official UI in some edge cases.

Input Simulation

Output follows the same philosophy — minimize fingerprinting:

- Keyboard input uses

SendInputwith scan codes (not virtual key codes), which is harder to distinguish from real hardware input - Text input goes through the clipboard (

Ctrl+V) rather than keystroke simulation, bypassing keylogger-based detection - Movement timing is randomized: jumps every 800-1600ms (Gaussian distribution), variable turn durations, human-like pauses between actions

Even the anti-stuck system has personality. When stuck, it escalates through increasingly desperate measures: 1. Jump 2. Sideways jump (randomly left or right) 3. Clear target, backwards jump, recalculate closest waypoint 4. Dismount, attempt direct movement for 10 seconds 5. If all else fails: use Hearthstone, teleport home, request a navmesh route to get back

4. Pathfinding: Detour + TSP Optimization

For most routes, the bots follow pre-recorded waypoint files. But for dynamic situations — getting unstuck, navigating to a gold order recipient, finding a corpse after death — they need real pathfinding.

WarrIO.NavMesh is a FastAPI server wrapping the Recast/Detour pathfinding engine via a compiled C# DLL called through Python's ctypes. It serves 630MB of pre-extracted WoW navigation mesh data — 1,291 tile files covering the game world.

POST /waypoints

Body: [[start_x, start_y], [end_x, end_y]]

Response: [[wp1_x, wp1_y], [wp2_x, wp2_y], ...]

The interesting endpoint is /route-smart, which solves a Traveling Salesman Problem for multi-waypoint routes. When a bot needs to visit multiple herb nodes or quest objectives, it optimizes the visit order using nearest-neighbor heuristic + 2-opt local search, then generates navmesh paths between each pair. The result is a near-optimal route through all objectives.

The navmesh server also handles a subtle coordinate system transform — WoW's internal coordinates are swapped (Y, X) relative to the standard convention. This caused three days of debugging before I figured it out.

5. The Coordination Layer: Redis Pub/Sub + Atomic Order Claiming

WarrIO.Server is the central nervous system — a FastAPI app backed by Redis (for pub/sub and caching) and SQLite (for gold transaction persistence).

It implements three core functions:

Inventory tracking. Each bot reports its gold and item counts. The server aggregates across connected WoW servers (some servers share auction houses and can trade between them). When WarrIO.Ebay needs to know if there's enough gold on Thunderstrike-Alliance to list an auction, it queries the server.

Gold order lifecycle. When an eBay sale triggers a gold delivery, the server creates a transaction order and publishes it to a Redis channel. All subscribed bots receive the notification simultaneously. The first bot to claim the order wins — using an atomic SQL UPDATE that only succeeds if the order is still in "open" state:

UPDATE gold_transaction_orders

SET order_state = 'in progress'

WHERE id = ? AND order_state = 'open'

If rowcount == 1, you got it. Otherwise, another bot was faster. Simple, no distributed locks needed.

Pathfinding delegation. The server also exposes the Detour pathfinding engine, so bots don't need direct access to the navmesh files. In production, the navmesh data lives on the server, and bots request routes over HTTP.

A background job runs every 5 minutes checking for transactions stuck in "open" or "in progress" for more than 20 minutes. If found, it emails me. This was the only human intervention point — and it rarely fired.

6. The Marketplace: eBay Automation with LLM-Powered Buyer Parsing

WarrIO.Ebay is where the pipeline meets the real world. It's a FastAPI application that manages the entire eBay selling operation:

Auction Management

Auctions are defined as JSON configuration — region, server, faction, gold amounts, prices:

{

"server": ["Thunderstrike_100"],

"faction": ["Alliance", "Horde"],

"gold_amount": [100, 200, 500],

"price": [6.95, 14.95, 40.95]

}

The system creates eBay inventory items, offers, and multi-variant listings through the eBay REST API. Every 10 minutes, it adjusts listing quantities based on actual gold reserves:

available_gold = warrio_server.get_gold_count(region, server, faction)

if available_gold >= gold_amount * 2: # 2x buffer

quantity = sold_quantity + 1 # Keep listing active

else:

quantity = 0 # Hide listing until gold is farmed

If a bot fleet gets banned and gold reserves drop, the auctions automatically disappear. When the bots recover, the auctions come back. No manual intervention.

The LLM Bridge

The hardest part of the pipeline was extracting buyer information from freeform eBay messages. When someone buys gold, they need to tell you their character name. But buyers write things like:

- "Hey its Thrall on thunderstrike thanks"

- "Charname: Arthas, Server: Ashbringer"

- "pls send to björk"

- "ive paid can u send to my alt Bankchar on razorfen"

Regular expressions would be a nightmare. Instead, I used GPT-4o with a simple system prompt: extract the character name and optionally the server name. The model returns "CharacterName;ServerName" or just "CharacterName" if the server is implied by the SKU.

response = llm_client.send_message(buyer_messages)

parts = response.split(";")

character_name = parts[0].strip()

server = parts[1].strip() if len(parts) > 1 else sku_server

If the LLM can't extract a name (buyer message is gibberish, or they're asking a question instead of providing a name), the system sends an error message to the buyer and emails me. This happened maybe 5% of the time.

The Full Order State Machine

order_received_and_paid

→ Send "What's your character name?" via eBay messaging

waiting_for_character_name

→ GPT-4o extracts character name from buyer reply

ingame_transaction_started

→ Bot claims order, navigates to mailbox, sends gold

→ Bot uploads screenshot

ingame_transaction_completed

→ Send confirmation + screenshot to buyer

→ Mark eBay order as fulfilled

Background jobs run on tight schedules: order detection every 2 minutes, pending order processing every 1 minute, quantity updates every 10 minutes, exception reports every 30 minutes.

The eBay Marketplace War

eBay itself had no problem with virtual goods selling — it was a legitimate product category. The challenge came from competitors. The WoW gold market on eBay is dominated by large-scale Asian resellers who buy gold in bulk from farming operations and resell at markup. They're middlemen.

I was selling direct — gold farmed by my own bots, from clean IPs, undetected accounts, no association with banned bot networks. Cleanest product on the market. And I was undercutting the resellers.

Their response: weaponized eBay's reporting system. They'd report my listings for fabricated policy violations — "image doesn't comply with guidelines," "misleading product description" — anything to trigger automated reviews and temporary listing removals. It's a known tactic in competitive eBay niches. The reports had no merit, but the automated enforcement system doesn't care about merit on the first pass.

This is what eventually made the selling operation unsustainable — not Blizzard's anti-cheat (which never caught me), but marketplace competition using platform rules as a weapon. A problem that better engineering can't solve.

7. Fleet Management: 18 Bots Across 2 Infrastructure Types

SocketPulseHub orchestrates the fleet — a lightweight FastAPI app that serves bot configurations and distributes updates.

At peak, I ran 18 simultaneous bot instances across GPU-VPS cloud instances and local Intel NUCs, each running 12-16 hour daily farming windows.

Each instance has a JSON config defining its schedule, bank character, and startup parameters:

{

"BotAgentExecutable": "WarrIO.Main.exe",

"BotAgentConnection": "tcp://localhost:13337",

"BotAgentStartupCommands": [{

"Type": "Action",

"Name": "InitializeWarrIO",

"Arguments": {

"startTime": "21:30",

"hours": "16",

"bankCharacter": "Bankschnecke"

}

}]

}

Deployment is pull-based: bot agents periodically check the hub for new versions of the behavior trees or bot executable. When I push an update, all instances pull it on their next check-in. Infrastructure-as-code via Git — adding a new bot is adding a JSON file and committing.

The staggered schedules were deliberate. Most bots ran 21:30 to 13:30 (evening through morning), avoiding peak hours when more human players are online and reports are more likely.

8. Multi-Bot Coordination: Group Farming

Beyond solo farming, the system supports 4-bot group farming through the BotNetChannel layer. One bot acts as leader, the others as followers. They coordinate via SocketPulse connections between instances:

- Leader broadcasts waypoints to followers

- Followers send heartbeat "ready" signals every second

- Leader waits until all followers are ready before advancing

- Quest completion is tracked across the group — leader verifies all members finished before moving on

- Group lead can be transferred dynamically (if the leader gets stuck or needs to do something else)

The behavior trees have dedicated master/follower subtrees:

<Sequence name="MasterPlayRoot">

<IsMaster/>

<WaitForGroup/> <!-- Block until all followers ready -->

<!-- ... farming logic ... -->

</Sequence>

<Sequence name="FollowerPlayRoot">

<IsFollower/>

<AcceptGroupInvite/>

<WaitForLeader/> <!-- Block until leader gives waypoints -->

<!-- ... follow and assist ... -->

</Sequence>

What This Taught Me About Autonomous Systems

Building this system over two years crystallized several principles that I've since applied to every distributed system I've built:

Separation of concerns enables reuse. By keeping TreeNetRunner game-independent, I built a framework that could drive any game — or any system that accepts named commands and returns status codes. The same architecture maps directly to AI agent orchestration, industrial automation, or any domain where you need hierarchical decision-making with remote execution.

Behavior trees beat state machines for complex agents. State machines explode in complexity when you have dozens of states with conditional transitions. Behavior trees compose naturally — sequences for "do all of these in order," selectors for "try these in priority order," decorators for "invert this condition." The 120+ node types in WarrIO.Profiles would have been unmaintainable as a state machine.

Pixel-based protocols are underrated. The game state encoding trick — Lua addon writes values as pixels, external process reads pixels via GDI — is applicable far beyond game bots. Any time you need to extract data from a sandboxed application without injection or hooking, screen-based protocols work. It's how some modern RPA tools work, and it's inherently hard to detect.

Atomic operations simplify distributed coordination. The gold order claiming system uses a single SQL UPDATE with a WHERE clause. No distributed locks, no consensus protocols, no eventual consistency headaches. When your coordination primitive is simple enough, the system stays simple.

LLMs are the missing piece for human-facing automation. The entire pipeline was deterministic except for one point: understanding buyer messages. That single GPT-4o call turned a 95% automated system into a 99.5% automated system. The ROI on that one integration was enormous.

Infrastructure-as-code with Git is operationally elegant. Adding a bot is a JSON file commit. Changing a schedule is a config edit. Rolling back a bad deployment is a git revert. The entire fleet history is in the commit log.

The Architecture in Retrospect

Looking at it now, what I built is essentially a multi-agent system with marketplace integration — the same pattern that's emerging in AI agent frameworks today. The bots are autonomous agents with hierarchical decision-making. The server is a coordination layer with pub/sub messaging. The eBay integration is an API bridge to the real world. SocketPulseHub is a deployment orchestrator.

Replace "WoW bot" with "AI agent," replace "SocketPulse" with "tool calling," replace "behavior trees" with "ReAct prompting," and the architecture looks remarkably similar to what companies are building today for agent-based automation.

The difference is that I built this in 2023-2025 with C# and Python, not with LangChain and GPT-4. The patterns are the same. The engineering challenges — coordination, error recovery, state management, human interaction bridging — are identical.

That's the real lesson: autonomous systems are autonomous systems, regardless of whether the agent is a behavior tree or a language model. The hard problems are always coordination, reliability, and interfacing with the messy real world.

By the Numbers

| Metric | Value |

|---|---|

| Repositories | 8 |

| Languages | 3 (C#, Python, Lua) |

| Peak simultaneous bots | 18 |

| Behavior tree node types | 120+ |

| Waypoint route files | 337 |

| WoW zones covered | 25+ |

| Navigation mesh data | 630 MB (1,291 tiles) |

| Sensor types (pixel-encoded) | 150+ |

| eBay API integrations | 2 (REST + Trading XML) |

| Background job schedules | 4 (1-min, 2-min, 10-min, 30-min) |

| Times detected by Blizzard anti-cheat | 0 |